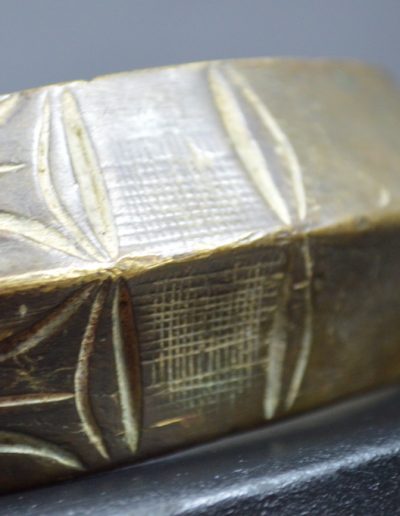

Fang Bronze Torque Necklace

Metal smiths assisted with them being applied to the neck of a woman who thereafter was unable to remove it. The torque was only removed after death.

Tribe: Fang

Origin: Equatorial Guinea

Approx Age: late 19th – very early 20th century

Materials: Bronze

Dimensions cm: 16.5 widest point x 4 depth

Ref. Number: 1641

£450.00

Description:

A fine Fang bronze torque collar from the Fang people of Equatorial Guinea. It is a solid cast rather than forged and has been gilded. It is heavy and would have been worn around the neck by a Fang woman. (Sometimes, they were also worn by men). Metalsmiths assisted with them being applied to the neck of a woman who thereafter was unable to remove it. The torque was only removed after death. This is cast in a ‘C’ shape and is heavily engraved with geometric motifs and carries a lovely old wear patina.

History

The Fang are best known for their wooden reliquary figures which are abstract anthropomorphic carvings. There are a few in collections that are still attached to the original relics they were meant to protect.

The Fang migrated into their current area from the northeast in recent centuries as small groups or families of nomadic agriculturalists. Their militant nature allowed them to seize land from their weaker neighbours as they moved in.

The peoples throughout this region of Gabon share similar political systems. Each village has a leader who has inherited his position based on his relationship to the founding family of that village. As a political leader, he often serves as an arbitrator and is equally recognized as a ritual specialist. This enables him to justify his position of power based on his relationship with the ancestors of the village. Each village consists of bark houses arranged in a pattern along a straight street, and the size of the village is often determined by the resources available.

The traditional religion of Fang centered around ancestors who are believed to wield power in the afterlife as they did as living leaders of the community. The skulls and long bones of these men were believed to retain power and to have control over the well-being of the family. Usually the relics were kept hidden away from the uninitiated and women. Wooden sculptures, known as reliquary guardian figures, were attached to the boxes containing the bones. Some believe that the figures are an abstract portrait of the deceased individual, while others argue that they serve to protect the spirit of the deceased from evil. It must be remembered, however, that it was the bones themselves that were sacred, not the wooden figures, thus there is no apparent contradiction in individuals selling what in effect was the tombstone of their ancestors for considerable profit to art dealers. During migrations the relics were brought along, but the reliquaries were often left behind.

References: IOWA art and life of Africa.

Ballarini, R., The Perfect Form: On the Track of African Tribal Currency, Galleria Africa Curio, 2009.

Bartolomucci, A., African Currency, Editore Africa Art Gallery, 2012.

Contact Exquisite African Art

Telephone:

+44(0)7531639829

+44 (0)1507 328026

Follow us

Subscribe to our mailing list

Website Design by Midas Creative